Collaboration: Chris Harrod @chris_harrod

The Chilean town of La Noria was a train station of the Nitrate Railway Co. that connected a number of bustling saltpeter works (Salitreras in Spanish) across the pampa in the region of Tarapacá - the 1920 census reported more than 9000 people living in La Noria. However, following the rapid and marked decline in the nitrate industry, the railway only continued operations until the 1930s, after which the inhabitants migrated en-masse to cities, such as Antofagasta, the modern regional copper-mining capital.

A similar story extends to hundreds of saltpeter works, that were scattered across the desert by the end of the 19th and the start of the 20th centuries. La Noria was home to workers that arrived from across Chile (and the World) both under their own volition or even many who were tricked (the “enganchados”) by tales of high wages. These newcomers transformed the region, extracting and processing nitrates from the desert, as well as working in the many industries required to maintain the saltpeter works in the desert.

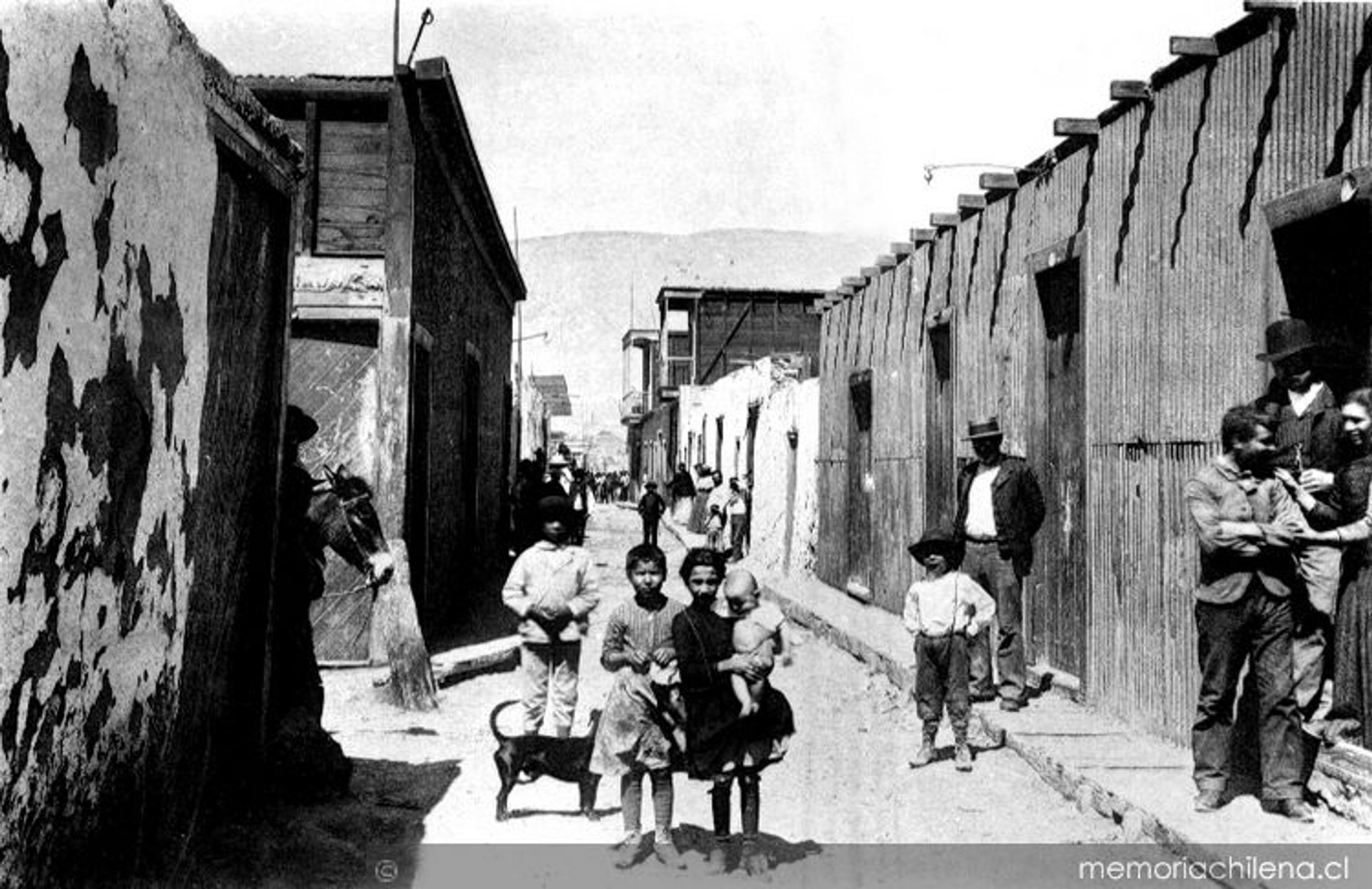

Children and residents in one of the main streets of La Noria town, Tarapacá, ca. 1910 (source: Memoria Chilena)

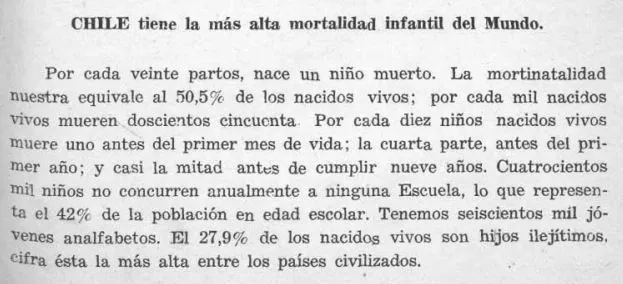

The Atacama Desert (which spans 1000 km and four regions, including Tarapacá were La Noria is situated) is one of the most extreme environments found on Earth – indeed it is seen as an analogue for Mars. As might be expected, workers in the saltpeter works toiled under extremely precarious working and living conditions that were shared with their families who lived onsite. The extreme conditions faced by the workers and their families included the highest solar radiation recorded anywhere on Earth, extreme water scarcity, stifling heat during the day and extreme cold in the night, bad sanitary conditions among others. Access to food, drink and medicine was controlled through the company store, with workers being paid in Company tokens, not cash. As might be expected, child mortality was staggeringly high (1): epidemics such as tuberculosis caused havoc in a period when the first national public policies on health were being formulated (2).

In simple words, survival in the salitreras was a struggle. This is probably most clearly emphasized by the thousands of tiny graves that can be found in the abandoned cemeteries that dot the Atacama Desert. Each child grave represents an individual tragedy, a life snuffed out before their time and heartbreak for their family. It is hard to visit these sites and not be moved. The cemeteries tell the story of the salitreras that extends beyond massive child mortality: plaques reveal that workers originated from across the world, and tell of how individuals died in work accidents.

Extract from La realidad médico-social chilena , Allende (1939) (3)

Although abandoned, the cemeteries still receive visitors: some return to tend graves of long-lost family, while others have more morbid intentions, and graves are vandalized and robbed. Others visit to leave things in the desert, taking advantage of the isolation.

Under this context, we do not know how a little girl came to be buried next to the church in the abandoned town of La Noria. We do not know if she was born alive, but we do know she was treated with care and love in her last moments, being carefully covered in a white cloth and a violet ribbon prior to her burial in a simple grave close to once consecrated ground.

[It was care and love in the last goodbye]

The harsh environmental conditions in the region result in the mummification of bodies, and they effectively become suspended in time. The rest of one little girl was interrupted in 2003 by a ‘huaquero’ (4), a person who scratches the desert’s surface hunting for treasure. Óscar Muñoz found the resting place of the girl: due to her extremely unusual and irregular appearance, he sold her for the grand sum of 30 000 Chilean pesos (40 euros). This attracted some local attention in the news media, but the discovery quickly spread across so-called ufology circles, with much speculation about the likely ‘extraterrestrial origin’ of the corpse. The body of the girl was re-sold to a Spaniard, Ramón Navia-Osorio who took her to Barcelona.

The subsequent odyssey of the body of the girl from La Noria has been cruel and tragic: UFO enthusiasts paid large amounts to take her photograph (one for €600, two for €1000), A documentary was made (Sirius) (5), X-rays were taken, she was referred to as ‘humanoid’… Finally, she was even exhibited as an object at a Ufology conference (Ufology World Congress, Barcelona, 2017).

A documentary was released in 2013 (6), in which the little girl from La Noria was shown both to be human, and of likely Chilean ancestry through the use of mitochondrial DNA sequenced from her bone tissue.

On March 22, 2018, a scientific article was published by a team of largely US-based, and well-renowned scientists in the journal Genome Research (7), which described the genome of the girl of La Noria, named ATA (Atacama humanoid skeleton). This study aimed to confirm her human character and to examine the origin of her malformations.

[She had a mother and a father: maybe she was called Paula or María]

The work published in Genome Research undoubtedly has value – it helps scientists understand associations between mutations and a case of malformation that has not been seen before. However, beyond the headlines, retweets and social media likes, some fundamental questions remain. For instance, the article does not make any mention regarding the existence of any permission or ethical consideration about the use of a human body for scientific or research purposes. Like many other countries, human remains and historical objects are protected by law in Chile, including the girl from La Noria. This protection comes from legislation passed in 1970 (N°17288) that protects National Monuments. Article 1 of this law states that “… Are national monuments and lay under the tuition and protection of the State, the places, ruins, constructions or objects with historical or artistic character; the burial or cemeteries or other anthropo-archaeological, paleontological or natural formation objects …”.

Simply put, to fulfil legal requirements to conduct the research described, a permit is needed from the National Monument Council. In addition, the DNA used for genome sequencing came from destructive sampling of some of the girl’s bones. As such, her body was damaged, illegal under Article N°38 of the law. Moreover, this regulation states that any study by foreign research groups using Chilean materials covered under this law must include Chilean researchers: no Chilean authors are included in the article (Law N°17288: Articles 22 and 23). It seems apparent that the researchers were ignorant of such requirements, but ignorance is no defence under the law. Again, collaboration with local researchers who are aware of the legal requirements would have solved these problems.

Beyond the legal requirements to undertake such work on samples from Chile, scientific journals typically require authors to make an ethical statement regarding the work described in their manuscript at the point of submission. Quite surprisingly, no such statement is associated with the study, and Genome Research seems to only require authors to ensure that materials are available to replicate the study. Beyond the lack of official permission, this fails to take into account the ethical complications of studies of human subjects sourced from a third country.

The article describes the genome of the girl from La Noria, allowing the authors to make predictions regarding her genetic ancestry. For this, they used databases detailing genomic information from different human populations, and the girl’s genes were an almost equal mix of South American and European origin. She grouped with South American populations, specifically those from the west of the continent.

The authors also described a series of previously unreported mutations and other information regarding the malformations exhibited by the girl from La Noria. They also reported genes related with cranioectodermal dysplasia and Greenberg skeletal dysplasia, which are coincident with the phenotype of the body of the girl of La Noria. The authors also noted that some associated malformations have been described previously in cases of consanguinity (incest).

The article is peppered by mistakes, revealing an unawareness of the wider context of the girl from La Noria, and where she was found. Many of these would have been avoided by discussions with local experts: probably more importantly, more would have been made of the data. Firstly, the article states she was found in the Atacama Region: La Noria is in the Tarapacá Region, more than 750 km to the north. A more important issue is that the authors associate an Andean origin with a genetic signature of people from the island of Chiloe (ca. 2 500 km south of La Noria). There is a large and ongoing body of work on Chilean human genetics led by Chilean scientists that the authors apparently did not make use of (8) (9).

The authors made the suggestion that because the body of the girl from La Noria was found in a saltpeter work, she was likely subject to prenatal nitrate exposure, which may have caused DNA damage (10) (11). However, La Noria was a service town, limiting the probable exposure to nitrates, which being found in rocks with other minerals (so called ‘caliche’) would likely not be particularly bioavailable. Humans have lived in the region for more than 8 000 years, and there is no evidence that nitrate poisoning has been an issue. A more pressing historical problem in the region was that drinking water was contaminated with arsenic.

The high quality of the DNA extracted from the girl from La Noria indicates that she likely died in recent decades: the authors suggest that this was up to 40 years ago, i.e. the 70s (a period of very marked unrest in Chile) (12). This is 40 years after the cessation of nitrate mining in the area and La Noria was abandoned in the 1930s. As such, it is very unlikely that the girl originated in La Noria, but was put to rest in there by people from another place.

[There in the Pampa, close to the old church, the little angel can go to heaven.]

The scientific article has had a major international impact in both news and social media. Headlines repeatedly highlight the “mystery of the alien of Atacama” has been solved, or that the “DNA of the fake alien of Atacama reveal her secrets”. No account has been made of the fact that this was a tragic little girl, born to Chilean parents who buried her next to an isolated, abandoned church. No attention has been paid to the important ethical issue that a team of leading scientists have undertaken a study on an illegally obtained human infant without legal permission.

What really happened was that the body of a girl with multiple physical malformations was disinterred and her body was exhibited. Out of simple respect for our fellow human, the current article in Etilmercurio does not include her photograph.

In a press release, one of the authors was quoted as saying “I think it (our emphasis) should be returned to the country of origin and buried according to the customs of the local people”. This fails to take into account that La Noria is now a ghost town. There is no acceptance that her body was used as an object for scientific research without any reference to the legal protection she was entitled by her country of birth.

The girl from La Noria has a mother, a father, maybe siblings. The mother, and possibly father would have been in great shock given the appearance of their daughter, yet they took her to La Noria to secretly bury her. What could be the destiny of these people? From the presumed timeline of her death, it is likely that her mother probably is still alive. Given the amount of interest about the case in the media, it is also possible that the family has been forced to relive events from forty years ago.

But, what is the current destiny of the girl of La Noria? A dark drawer in some place in Europe.

[The sun and its warm hands of consolation is waiting for you in the pampa]

Etilmercurio demands that the Chilean authorities, the academic community and civil society openly condemn the outrage continually committed over the years.

Stories like the girl from La Noria force us to think about the ethics of science, especially regarding how samples are obtained for analysis. From our reading of the information associated with the work, the authors have spectacularly failed in this regard. If samples are obtained unethically, any resulting science is not ethical, and as such, should not be published. If work has been published under questionable circumstances, a common reaction from a journal’s editors is to retract the article.

This case is only one of many known cases of the plunder and sale of mummified bodies. For instance, a website in the Netherland is controversially offering a mummy of a Chilean baby dated to 900 YBP for sale for €15000 (13).

Which is the value of a human body? Or, is dignity lost after some few decades after decease? Would these authors be happy working on the body of a surreptitiously-buried child from Boston, MA or Santa Barbara, CA? Or are the ethics of working on children from less-developed nations less complicated? This is important as the students that we teach, and that we mentor (as well as the Chilean Government) look to the US as a beacon of best practices. As such, we can expect better from our international colleagues.

Citations

1.

Jiménez, J. & Romero, M. I. (2017). Reducing Infant Mortality In Chile: Success In Two Phases. Health Affairs, Vol. 26, No. 2: Designing Children's Health Care. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.458. Disponible aquí.

2.

Herrera, T. & Farga, V. (2015). Historia del Programa de Control de la Tuberculosis de Chile. Revista chilena de enfermedades respiratorias, vol.31 No. 4, Santiago, diciembre 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-73482015000400009. Disponible aquí.

3.

4.

5.

La Tercera (2013). Documental revela misterios tras “alien” encontrado en el Desierto de Atacama. 24/04/2013. Disponible aquí.

6.

7.

Bhattacharya, S. et al (2018). Whole-genome sequencing of Atacama skeleton shows novel mutations linked with dysplasia. Genome Research. Disponible aquí.

8.

Fuentes, M. et al (2014). Geografía génica de Chile. Distribución regional de los aportes genéticos americanos, europeos y africanos. Revista médica de Chile, vol.142 no.3 Santiago mar. 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0034-98872014000300001. Disponible aquí.

9.

Eyheramendy, S. et al (2015). Genetic structure characterization of Chileans reflects historical immigration patterns. Nature Communications volume 6, 17 March 2015. doi:10.1038/ncomms7472. Disponible aquí.

10.

Andreassi, M. G. et al (2001). Chronic long-term nitrate therapy: possible cytogenetic effect in humans? Mutagenesis, Volume 16, Issue 6, 1 November 2001, Pages 517–521, https://doi.org/10.1093/mutage/16.6.517. Disponible aquí.

11.

Andreas, D. & Thomas, M. (2015). Organic Nitrate Therapy, Nitrate Tolerance, and Nitrate-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction: Emphasis on Redox Biology and Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants & Redox SignalingVol. 23, No. 11, https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2015.6376. Disponible aquí.

12.

Anarte, E. (23 de marzo de 2018). Ata, la momia de Atacama, era un bebé humano y por fin podrá descansar en paz. http://www.dw.com. Disponible aquí.

13.

Emol (05 de marzo de 2018). Arqueólogos indignados por venta de momia chilena de 900 años en tienda-museo holandesa. Emol.com. Disponible aquí.